What LLMs Actually Read When They Answer a Query

LLMs don't read the internet like humans. Understanding what they actually consume is the difference between guessing at visibility and engineering it.

One of the most persistent myths about AI search is that it “reads the internet.”

It doesn’t. Not in the way people imagine.

When an LLM answers a question, it is not browsing the web like a human, clicking links, weighing arguments, and forming an opinion. What it’s doing is far stranger and far more constrained.

Understanding those constraints is the difference between guessing at visibility and engineering it.

The illusion of reading

Humans read sequentially. We follow arguments. We notice tone shifts. We remember sources.

LLMs do none of this.

They do not read pages. They operate on representations of text—compressed numerical forms that preserve patterns, not intent. When a model appears to “know” something, what it actually knows is that certain language patterns reliably co-occur with certain questions.

This matters because optimization for AI search is not about persuasion. It is about compatibility.

The system is not asking whether your content is convincing. It is asking whether your explanation fits cleanly into its internal map of how ideas relate.

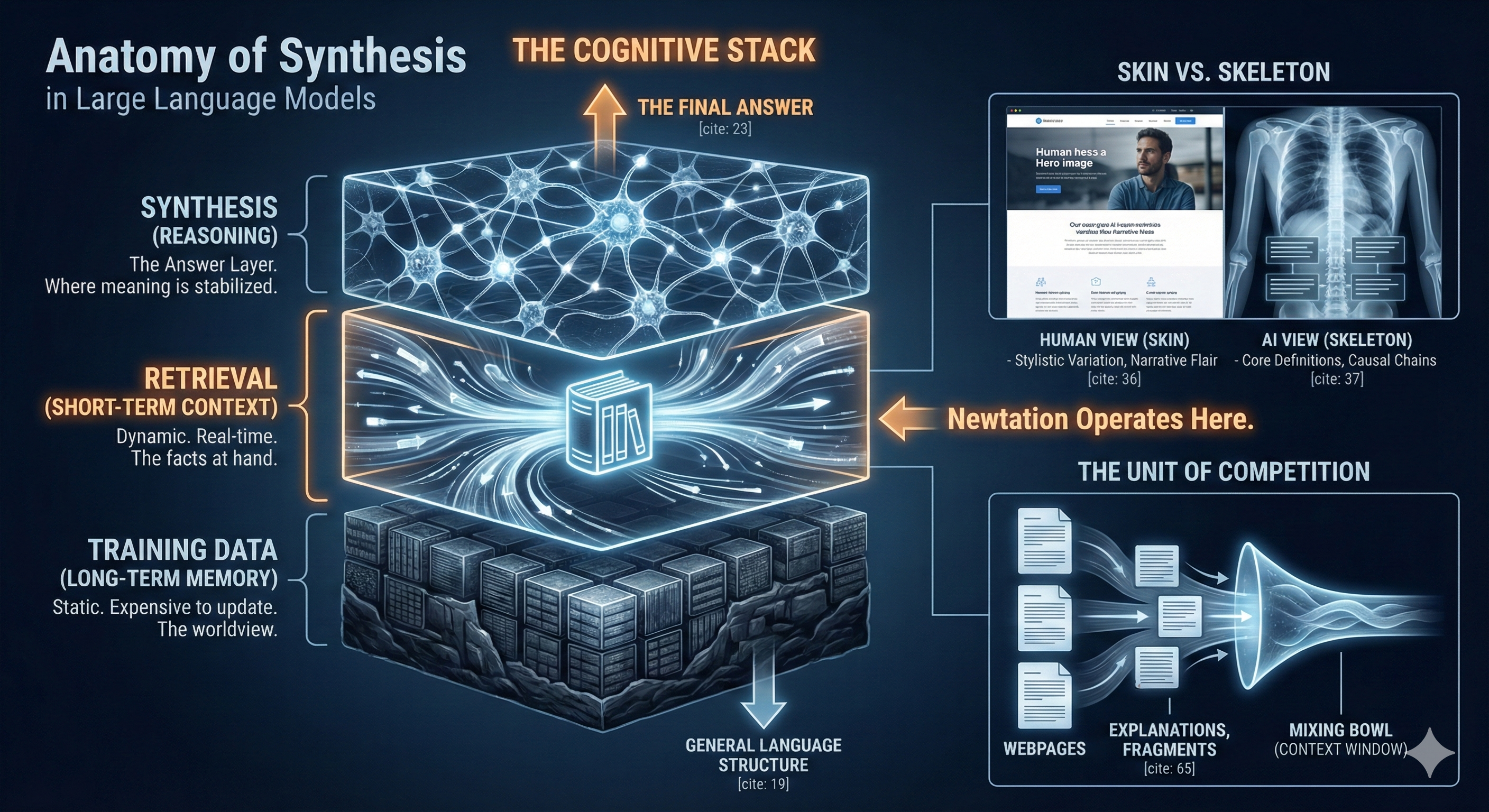

Three layers people conflate (but shouldn’t)

Most confusion around AI search comes from collapsing three very different layers into a single mental model.

First: training.

This is where the model learns general language structure and broad associations from massive corpora. You do not influence this directly or predictably. Thinking you can tactically “optimize” for training data is a category error.

Second: retrieval.

Some systems fetch external documents at query time. This is where accessibility, freshness, and semantic relevance still matter. But retrieval does not behave like traditional ranking. It selects candidate material; it does not order winners.

Third: synthesis.

This is where the final answer is composed. Multiple sources are blended. Language is normalized. Idiosyncrasies are smoothed out.

Most brands focus on the wrong layer.

They either chase training data they cannot touch or assume retrieval behaves like classic SEO. Meanwhile, synthesis quietly determines what survives.

What actually survives synthesis

Synthesis is a ruthless filter.

Anything that cannot survive paraphrasing, summarization, or recombination does not make it through. The system is constantly testing a silent constraint: can this explanation be reused safely?

This is why certain patterns dominate AI-generated answers:

Clear definitions outperform clever phrasing.

Stable terminology outlasts novelty.

Explanations that work across contexts beat edge cases.

This does not mean creativity is punished.

What must remain consistent is the skeleton, not the skin.

Human-facing content can still have voice, tone, narrative flair, and stylistic variation. What cannot vary freely are the underlying elements: core definitions, causal structure, and the distinctions you want the system to learn.

If you explain the same idea five times with five stylistic variations built on the same structure, the system sees reinforcement.

If you explain it five times with five different underlying structures, the system sees disagreement and averages you into weakness.

You are not optimizing prose. You are stabilizing meaning.

How engineers actually deal with black boxes

When systems stop being interpretable, engineers do not try to pry them open. That impulse belongs to auditors and philosophers, not people who need systems to work.

They change methods.

Instead of asking what is inside, they ask a more useful question: how does this system behave, consistently, under different conditions?

This is not guesswork. It is applied empiricism.

Inputs are varied deliberately and outputs are observed over time. Patterns are tested across prompts, contexts, and phrasings. Explanations are checked for whether they survive paraphrasing, summarization, and recombination. Sources are examined for which ones are repeatedly drawn from and which are silently ignored.

What this builds is not an explanation of the model. It builds a behavioral profile.

That profile reveals what kinds of language the system treats as stable, which framings it reproduces versus rewrites, where it becomes cautious or evasive, and what it treats as safe knowledge rather than speculative claims.

Engineers do this with compilers, networks, distributed systems, and recommendation engines. They do not need perfect interpretability. They need predictability at the margins.

AI search is no different.

How sources are treated (and mistreated)

From a human perspective, attribution feels essential. From the system’s perspective, it is optional.

LLMs do not care who said something first. They care whether something is said consistently enough to be trusted.

If your explanation aligns with others, it is absorbed.

If it is useful but unique, it may be diluted.

If it is unique and brittle, it disappears.

This is not theft. It is consensus compression.

The system keeps what overlaps and discards what does not generalize.

The unit of competition is not the page

In AI search, pages do not compete. Explanations do.

The system evaluates fragments: definitions, examples, causal chains, distinctions. Each fragment either fits cleanly into an answer or it does not.

This is why sprawling content often underperforms. The more inconsistent your explanations are, the harder they are to reuse.

You do not win by saying more. You win by saying the same thing clearly, repeatedly, in compatible ways.

Where brand still matters

Saying you cannot optimize for training data tactically does not mean brand presence is irrelevant.

It means the timeline is different.

In the short to medium term, the only meaningful lever is synthesis. You make your explanations reusable now.

Over the long term, explanations that propagate widely and consistently increase the probability of being absorbed into future training corpora.

Training data is not a lever. It is an outcome.

Brand still matters. It just compounds slowly and rewards consistency rather than bursts of visibility.

The quiet strategy underneath

Once you understand what LLMs actually consume, strategy becomes calmer.

You stop asking:

Did this page rank?

Did we get traffic?

Did the algorithm like it?

And you start asking:

Is this explanation reusable?

Does this framing survive compression?

Are we consistent across contexts?

Those are not marketing questions. They are engineering questions.

The closing reality check

LLMs do not read like humans.

They do not reward originality the way humans do.

They do not care about intent.

They care about whether your ideas can be compressed without breaking.

If you design for that constraint, visibility follows—even if you never see it happen.

That is not comforting.

But it is accurate.